Planning Change is Easy, Making Sure it Sticks Is Not

Add bookmarkA Six Part Framework to Embed Change

Look around any ‘change’ library and you will find tonnes of literature on planning change and its first phase implementation, writes contributor Arnab Banerjee. But look for words on making sure the change sticks, and the shelves are bare. In this article, Arnab describes how he created a framework to embed change by customising a 6 Sigma methodology.

A well-known writer on change management once commented, ‘the front end of change is for the rock star. This is where the rewards and recognition lie. This is where most human resources management systems provide reinforcement. But the back-side, or late stage of change, is different. It's for the roadie. Indeed, most of the incentives have dried up, the thrill is gone and it comes down to grinding discipline and unrecognized and inglorious execution to take the initiative the distance.’

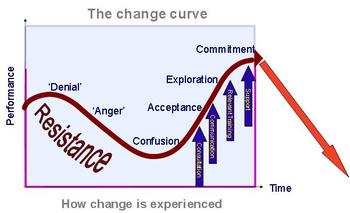

To make use of the popular change curve (Fig. 1), most change initiatives stop at the top of the curve; following an initial phase of implementation where all is assumed to be ‘frozen’ and the change team walks away. The support to delivery teams / front line staff is removed and the change is often not implemented deeply enough.

Fig. 1 – the usual Change curve and what often happens next

Let me illustrate.

Picture this: a large infrastructure organisation with an annual spend greater than £1B. At any one time there are more than three hundred projects active. On those projects, there are over two thousand project professionals – project managers, engineers, construction managers, risk, planning, cost, commercial, document controllers - spread across five business units.

Now imagine trying to make change stick within a business like this.

That was the situation confronting the organization I work for when we started rolling out a project management methodology to replace multiple local practices. We wanted to create a framework with a common vocabulary to enable improved delivery. The challenge was that many similar changes had been tried before and failed for one reason or another. We had gone through the classic change curve illustrated in Figure 1, followed by the corresponding drop off in commitment.

Staff met our latest initiative with scepticism. A Business Users’ Group – members of front line delivery teams – was set up at the very start of the change project and, at one of the first meetings, a Senior Project Manager asked, ‘this is the fourth time in seven years that we have been in a room like this with people like you telling us to change. How is this different?’

Albert Einstein once said that the definition of insanity was doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. So we needed to do something differently, but the question was what?

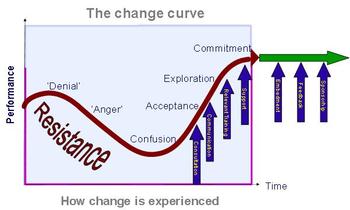

First, we changed how we thought about the change curve. It was clear to us that the timeline had to be extended and the commitment to the change had to be visible, active and continued, even once we’d achieved initial implementation.

Fig. 2 – The change curve with the "Arnab Continuum"

The target in this case was not just to make the change, but to see it through and make sure it didn’t fail even after the music had ended, the lights had gone out and the screaming fans had gone home. We were committed that this time really would be ‘different’.

But I still had to find a practical approach to extending this change curve. I could find nothing useful in my initial literature review. But a friend and former colleague pointed towards the George Eckes[1] book on Six Sigma implementation. I read it cover to cover and adapted the various chapters into a framework that could be used to embed change.

Below is the framework I used for embedding the change based on George Ecke’s principles. If you have a better one, please get in touch!

|

# |

Category |

What it means for the embedment project |

|

1 |

Creating the Need / Making a Difference |

Supporting project teams at their desks to work through the transition and meet the needs of the updated methodology. Showing the advantages of the new system through many, many 1:1 interactions. Collecting examples of beneficial consequences and spreading the word. The best change sells itself but good case studies are always beneficial. Maintaining a support service long after initial implementation so that users could provide improvement suggestions. Over 900 were received in the twelve month period following release and each received a response. Our Lesson: Don’t underestimate the need for individual support in major change programmes. And keep it going. |

|

2 |

Shape a Vision |

Agreeing and having all business units sign-up to an implementation plan appropriate to itself. What does a fully embedded system look like? In terms of training, business as usual structures, roles and responsibilities. A target date of October 2010 (following release in July 2009) was set whereby the business units would be running the methodology with minimal support from the change team. This was mutually agreed and achieved. Our Lesson: Even a business-wide change will have local nuances and have local teams buy up to this – get that involvement. |

|

3 |

Mobilise Commitment and Overcome Resistance |

This was directly linked to category 1 above. Make life easier and, more often than not, the change will be supported. A lot of the groundwork for overcoming resistance was laid down in the development phase when hundreds of professionals were consulted. A groundswell of support was created. Following release, within one month, there had been ninety engagements – ranging from a few to the largest with over three hundred. This was followed up with many hundreds of individual interventions. Our Lesson: One that is taught in every change primer: articulate the, ‘what’s in it for me?’ But, in this case, we didn’t just say this at the start of development and nor did we leave it at a handful of pilot projects. Following release, we sat at people’s desks and helped them become familiar with the system and worked with stakeholders to develop behaviours. And, as stated above, took many improvement suggestions and had them implemented. |

|

4 |

Changing Systems and Structures to Support the methodology |

This was a critical element of embedment. A project management methodology must take into account a range of functions including, in particular, Engineering, Procurement, Planning, Risk and Health and Safety. Each of these areas was required to develop clear definitions of what would be required from project teams. Functional representatives then presented and explained these elements to project teams rather than members of the change team – thus building ownership and accountability. In addition, corporate systems – SAP, Primavera – had to be consistent with the methodology. The objective was to create a ‘whole’ methodology which meant that there was consistency across the entire environment of delivery. Our Lesson: Little change can be done in isolation. What else does it affect and, for the user, is there consistency across organisational and functional boundaries? |

|

5 |

Measuring acceptance |

This is the assurance side of change. Firstly, a series of audits was carried out by the Internal Audit function (independent of the change team) focusing on critical aspects of embedment and, secondly, there was an external P3M3 assessment. For the Level 3 certification, twenty-nine 1:1 interviews were conducted and 230 questionnaires were returned from 660 sent out. Our Lesson: An external assessment focuses the mind! Be brave and check on embedment – do not assume that all is well! |

|

6 |

Visible Leadership |

Another basic point from the change management canon. This was not a management team that was passionately focused on the change – with one or two notable exceptions – and symbolic CEO-led statements of purpose were not possible. However, the project leader was provided with the funds to maintain the change team following first phase implementation and this was critical. The change team focused at a more mechanical level. We helped business unit leaders to: agree local implementation plans, set up business-as-usual structures by October 2010, write e-mails stressing the importance of this project, brief management meetings, send out invitations to communication events andunderstand stakeholder issues in their respective areas. Our Lesson: In a culture of CEO-led interventions and good corporate obedience, management support can be a given. In other environments, be prepared to be ‘in the faces’ of senior management and continually work with them to obtain the necessary high level and visible support. Conflicting demands on time requires that change teams spend time with the top layer and address concerns. |

Table 1: Adapted from Making Six Sigma Last – Managing the Balance between Cultural and Technical Change, George Eckes, Wiley and Sons, 2001

Did the framework work for the project? I’m quite happy to report that although it took time for the change to really set in, this time really was 'different'!

In December 2007 we had an initial measurement of Level 1 on the P3M3 maturity scale (spans level 1-5) – characterised by lots of local, inconsistent practices. By March 2011, the organisation achieved independent Level 3 certification – which meant uniform practice documented with good evidence of adoption and embedment across all business units. This has led to significant quantitative and qualitative benefits to the organisation. If you'd like to read the full case study you can read it here.

Will the framework work for others? I certainly hope so, but there are, of course, all types of change projects. This was one where there was a genuine need and the product being sold would, it was felt, be of benefit to front line teams and the business. We were lucky in that there was general support for the change and change management principles could be adopted from the start.

Other changes are more difficult - for example, restructuring and the reduction of people. In these instances, at the front end, the vocabulary of change management is often used – incorrectly - to provide a patina of consultation when, in reality, the change has already been set and will be carried out without modification.

However, I believe the embedment framework remains important regardless of the type of change.

Any major change of this nature, which affects the working lives of thousands of people, needs three elements: (i) a clear rationale, (ii) a good ‘product’ and (iii) sufficient management support to see through the embedment phase which involves significant training, communication and support to users.

Conclusions

The necessity of maintaining a single-minded focus on embedment cannot be emphasised enough. The timeline for embedment should be just as long as that for development and initial release. So, if it takes twelve months to develop, release and complete an initial phase of wide-scale roll out, be prepared to maintain the change team for at least another twelve months to embed the change successfully.

[eventPDF]

References:

[1] Making Six Sigma Last – Managing the Balance between Cultural and Technical Change, George Eckes, Wiley and Sons, 2001