The Seven Tenets of Process Management

Add bookmark

Think you are a process-oriented organization? In this article, Michelle Cowan and Jeff Varney from APQC, describe the seven characteristics of a process oriented company and explain how to get started yourself.

Before jumping into any kind of re-engineering or improvement efforts, organizations need to stop and take two actions: (1) identify how well the organization is performing in specific areas, including both its weaknesses and strengths and (2) determine where the organization's ideal future state should be. Only then, can business leaders map out a trajectory from current to ideal state.

This is never more true than when trying to increase process management maturity. APQC typically offers two basic assessments an organization can try either as precursors to a more detailed assessment or as tools to structure deep-dive assessments leaders already want to make. Let us look into both assessments: one based on APQC’s Seven Tenets of Process ManagementSM and another that looks at an organization's foundations in functional or process-based thinking.

What are the Seven Tenets of Process Management?

APQC’s Seven Tenets of Process ManagementSM encapsulate the common characteristics exhibited by successful process-managed organizations. By assessing an organization’s current state using the seven tenets, leaders can better discern which activities and strategic decisions will move the enterprise toward more mature and streamlined process management practices.

Once the assessment is complete, you can determine what basic changes can be made in each of the seven areas that will drive performance and ultimately increase the organization’s process maturity. By considering all seven tenets, leaders can feel confident that process management plans address the organization holistically and will support a smooth and efficient transition from the old ways of doing things to the new.

The seven tenets are:

- Strategic alignment—how well process management is linked to organizational objectives;

- Governance—how accountability for process activities is assigned and what structures are in place to support those involved in process efforts;

- Process models—structures, definitions, and knowledge resources designed to help the organization gain a common understanding of its processes;

- Change management—approaches developed to move employees and work activities toward a process focus;

- Performance and maturity— how well processes are performing and how mature process management is in every area of the business;

- Process improvement— strategies and initiatives to improve processes and learn how to continuously optimize performance; and

- Tools and technology—the software applications, Web portals, and print materials available to help the education and management of processes.

Best-practice organizations identified by APQC over the years have consistently excelled in these seven tenets. Top organizations may not be perfect in every area, but their process management approaches explicitly address all seven tenets, ensuring that the organizations can move smoothly toward process alignment.

Once you understand your organization’s capabilities in all seven areas, you must identify and prioritize the steps needed to implement the kind of process capability you envision. It is essential to make sure that the steps you take (and their expected impact) align with your strategic goals and objectives. This includes performing a reality check to ensure that process management plans do not conflict with other initiatives and projects across the business.

Function- or Process-Based?

Before embarking on a process maturity assessment, it is often helpful for an organization to determine how process-oriented it is. The following categories loosely define most organizations, from more functional-based to more process-based.

- Functional-based organizations are hierarchical in practice and manage people within the context and boundaries of their specific tasks, without necessarily considering the other process activities that affect or are affected by those tasks. These organizations are often referred to as "vertically oriented" instead of "horizontally oriented." Often, the business is organized around functions, products, regions, or operations. The organization exhibits little process management capability, but pockets of process knowledge and excellence may exist. Functional organizations often find it difficult to respond to rapidly changing markets and customer needs.

- Process-thinking organizations conceptualize groups of activities as processes and seek to understand how all of the processes in the organization work together to take inputs and produce products, services, and profits. Process thinking leads to the development of definitions and the documentation of processes, but does not involve action to fully integrate those definitions and process designs into the culture and the business. A comprehensive process framework and process management infrastructure do not typically exist.

- Process-focused organizations integrate, design, and manage end-to-end, customer-driven processes that are tied to functional activities and goals. A comprehensive process framework and process management infrastructure exist. The focus for management shifts from hierarchical to horizontal management. Process-focused organizations take action to integrate process thinking with the organizational structures (functions), business objectives, and people already in place.

- Process-based organizations reorganize and manage completely around processes, with an end-to-end focus on workflow that creates value for the customer. Functional activities are embedded in the processes, and individual senior executives are assigned responsibility for specific inter-enterprise processes. Process-based enterprises organize work starting at the customer interface and ending at final service or product delivery. An example of this is the "procure-to-pay" process. This process begins with a customer request for a product/service and ends with the final invoicing of the customer, involving a complete integration of finance, sales, and supply chain.

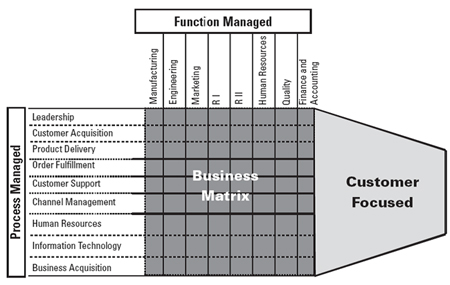

After identifying with the category most reflects the organization, leaders can determine which category they would like to be a part of. This decision depends on the organization's needs. Becoming process-based does not make sense for every organization. In fact, most organizations operate under a matrix management model that overlays process-based management on top of existing functional or product-based infrastructures. Paul Harmon’s[1]function-process matrix provides clarity on what the evolution from functional and process-thinking to process-focus looks like (Figure 1). The function-process matrix lists functions or departments on the horizontal axis and value chains or business processes on the vertical axis, showing which functions are involved in which processes. Figure 1 specifically represents function/process relationships at Deere & Co.

Harmon's Function-Process Matrix Applied at Deere & Co.

Figure 1

An organization may choose matrix management as its goal and, as a result, build toward a process focus. Others may desire a more fully process-based approach with an organizational structure aligned around the key processes of the business. The objective depends on the particularities of the organization, its structure and culture, and the industry in which it operates. Some organizations may be so functionally entrenched that it would not be feasible to consider a shift to process-based management. Other business structures may lend themselves to a stronger process approach. No matter which structure is chosen, the interplay between process and function always exists and must be managed to achieve high performance.

Knowing where your organization falls on the function/process spectrum can help when planning for the future and determining the goals for more detailed current-state assessments.

How to Create an Action Plan?

Employees performing these assessments may or may not be responsible for developing a plan of action to address any issues or begin new process management initiatives. The bottom line is that someone needs to take action on the assessment. The entire evaluation is merely an intellectual exercise unless the organization makes moves to align, optimize, and maintain processes throughout the enterprise. The action plan should build upon the report and the data it contains. All actions should be validated by verified information.

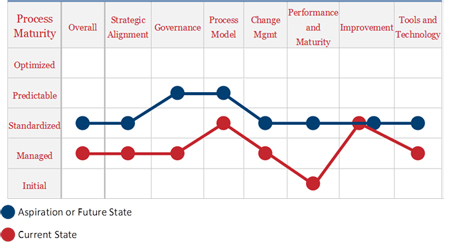

One way to structure a plan of action is to map the current state of the organization and then project the desired future state. Figure 2 illustrates a mapping of present and future states for an organization that completed its assessment using APQC’s Seven Tenets of Process Management as a guide.

Figure 2

Note that, in one area, the organization simply wants to maintain its status. This projection may be for the next year or multiple years, depending on how quickly the organization believes it will complete the steps to achieve its next desired level of process maturity.

However quickly you anticipate seeing improvements, plan the progress you intend to make and track your movement toward those goals.

Conclusion

Before undertaking any process management initiative, an organization should perform an assessment of current capabilities so it knows where to start. Evaluate your organization’s capabilities, noting where you are and where you would like to be. Consider how process or functionally focused the organization is, and determine what a realistic goal would be for increasing management by process. Would your organization work best with a matrix model, totally process-based management, or some other scenario? Then, create a methodical plan for achieving that end state. An approach that assesses your present state against external and internal standards will ensure that the process management initiatives you select will create value for the organization and lead to a more streamlined and profitable business.

Editor's Note: This article has been reprinted with permission from APQC, a member-based nonprofit and a proponent of benchmarking and best practice business research. Working with more than 500 organizations worldwide in all industries, APQC focuses on providing organizations with the information they need to work smarter, faster, and with confidence.

[1]Paul Harmon is chief consultant and founder of Enterprise Alignment, a professional services company. He is also the author of Business Process Change: A Manager's Guide to Improving, Redesigning, and Automating Processes (2003).